History: Our Linguistic Dream

We've created history. We've created a linguistic narrative.

Sounds ridiculous, childishly obvious, right?

But try to conceive of life, the human experience, outside of history?

How would you express all you've lived to someone without describing events? Without using language? How would you describe your experiences without dates and periods, descriptions, and stories?

You'd feel like you never existed.

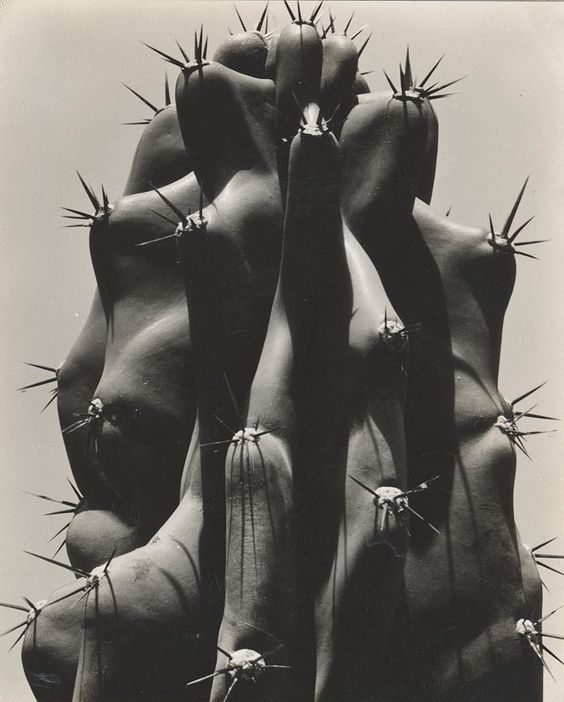

It would feel like shaky ground...Like that first moment when psilocybin begins to contort the objects around you, and the absurdity of the mundane hums with an otherworldly radiance.

Any purveyor of the great plant teachers has found themself stunningly enchanted by simple, everyday objects that have passed us by in normal waking consciousness.

We feel petty, ungrateful, vulgar in the newfound presence of a resonance that we've stifled behind letters.

Because when we try to express and explain our individual and collective experiences outside the domain of history, words begin to evade us.

They return to their ethereal mother. We are tripped up by the very language we are using to support our experience. The scaffolding of our constructed reality (Culture).

We realize that we cannot exist in our mental paradigm without language, like a child repeating a word and inevitably discovering its utter meaninglessness. It becomes a porthole into the abyss of the true nature of reality beyond language and history. The very same experience the Rishis were experimenting with when they developed their ancient mantras.

We start to realize that when our history is pushed to its parameters, even the Neolithic had narratives, mythologies, and shared stories about their societies and worldviews.

We begin to venture into that Edenic landscape that we've naively and arrogantly believed our childish, god-fearing ancestors churlishly fabricated.

Well, perhaps they understood more about reality than we give them credit for.

Perhaps our ancestors understood reality in such a way that it would put most self-respecting shrinks out of business.

Because we cannot conceive of our reality without language. Without a history.

This, in my opinion, (aside from power) is why monotheistic religions have so vehemently opposed shamanic and indigenous cultures. Monotheism relies on history, whereas many shamanic traditions, such as the Indigenous Australians, traditionally inhabited a world where language and history were very loosely intertwined with concepts of time.

Theirs was a cyclical worldview: From the micro to the macro, the individual seamlessly merged with the collective.

However, our history depends on linearity, time, and language. It depends on thought agreements.

Because history itself is just a narrative, right?

His-story.

A yarn. Our beautiful and terrifying cultural dream. And one where objectivity is, at best, an ideal worth striving for.

Traditionally, for most of human history, we were told what certain people, certain powerful people, wanted us to believe. Control the mythologies and the language, and you control history. Control history: you control reality.

And certainly, ol' Guttenberg probably pushed us further towards objectivity than anyone had since the invention of language itself. Thank God he gave the polished mirrors a miss and invented the printing press, kick-started the reformation, ended the cultural monopoly of the Catholic Church, and set the fires burning that would eventually fuel the Enlightenment.

Because the invention of affordable printing methods paved the way for an explosion in information on a level human society had never seen.

Previously, perhaps only since the great matriarchal temples of Minoan Crete Western civilization could share subversive ideas free from the censorship of the religious and political elite. It snatched the syntactical power out of their hands and created the blueprint for a world so connected that we now (in Western Liberal democracies at least) have greater access to information than all the emperors who have lived and died on this planet.

A 5-year-old with a 10-euro phone plan has more access to knowledge in their pocket than Queen Victoria or Kennedy.

But what's happening here?

What is it that we have access to? What is information?

Well, if you look at it closely, it's another ouroboric synonym for history. It's the collective record of our lived experiences. A collection of opinions, perspectives, and mutually agreed-upon facts.

Because even the hardest "truths" are linguistic agreements at their core. Time, gravity, and biology all rely on linguistic agreements. They depend on and thrive on history.

Because although we can observe distant planets in motion, call each other in real-time, and read a month-by-month account of life in ancient Rome, we still have no idea what exists outside of our constructed linguistic reality. Everything else outside of language relies on the felt presence of direct experience. The transcendent, which can only be lived, is not explained away by babbling monkeys.

Even now, in writing this, I am eternally tethered to language as a way of transferring my reality. But it isn't The Reality, is it? The moment language enters, there's a buffer.

Culture cannot exist without history. History creates timescales, and language constructs the framework for our ever-shifting understanding of our reality, from the morning events to the deepest truths we hold about the nature of the laws of physics.

While this seems obvious to the point of absurdity, the realization that our history and language form the framework for our reality and that we cannot define a reality outside of these two monumental gatekeepers is obvious in strikingly common moments. Glitches where language is snatched from us, and we are faced with the totality of the sublime knocking on the doors of syntax.

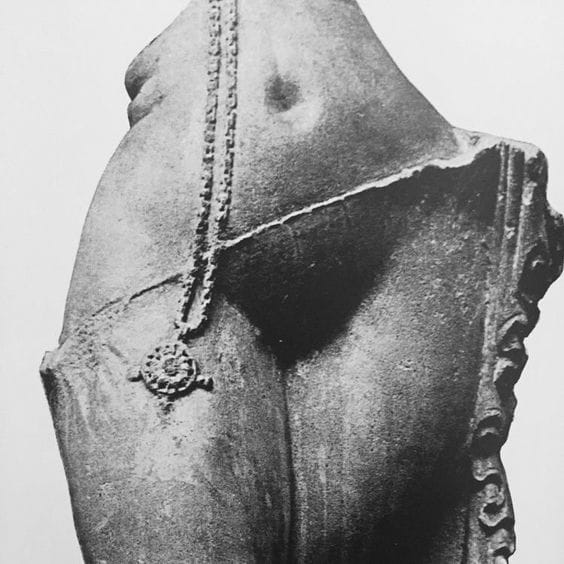

Joseph Campbell called this the experience of "Awe." William James recognized these moments as mystical experiences. Instances where we find ourselves pitifully incapable of verbalizing or cognizing the ineffable. The terrifying power of nature, the sound of the jungle static, orgasm, music. Moments where the crack in the fabric of our constructed reality splits open, and we are confronted with the raw, unfiltered magnitude of the primordial energy.

It's Samadi; it's Zen. It's Christ consciousness. It's Arjuna cowering at the feet of Krishna's true nature. Those wonderfully human moments where the absurdity of life presses against us momentarily. Where words return to squiggles and dots, and we are briefly returned to Eden, outside of our cultural confines.

We need to see the limiting potential of language and that our history, our culture, is a lattice of linguistic agreements.

Culture is nothing more than the repetition and record of language: A semantical matrix. Beyond this lies the true nature of reality, the howling void, the great Tao.

Beyond history,

beyond time,

beyond all language.

It can only be experienced by direct contact with the indescribable.