Afternoons With Marjane

And we'd sit in her dingy little kitchen drinking rose tea, watching the steam from the Persian rice gently coiling into arabesque calligraphies as we fumbled through lost translations spaced between curiously comfortable silences.

Mostly, I'd listen. My accent transfiguring even the simplest questions into a misunderstanding.

It was better that way. And on her more lucid mornings, when the pills hadn't yet scrambled her brain and memory hadn't betrayed her, she'd talk of her life in Tehran, the early years before the revolution.

And always, a vacancy would transform into a sad, sweet smile as she recalled her student days, studying language and literature at university, courting Bahram, and becoming a professor.

"We were free then," she'd softly say. "Freer than Europe."

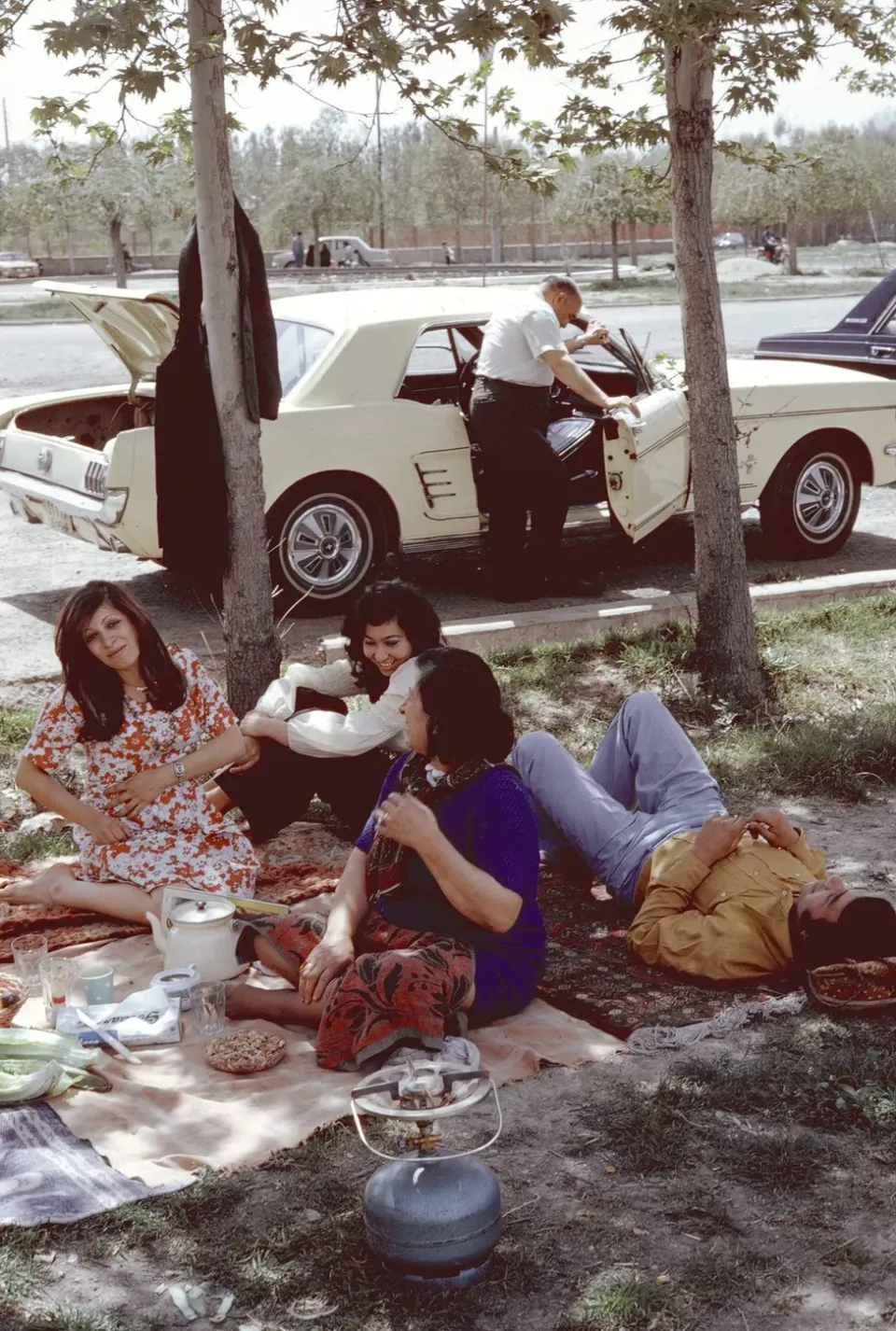

It was true; I'd seen the photos.

The faded polaroids couldn't hide the miniskirts, high leather boots, eyeshadow, and the giggling, hashish-fueled picnics.

Tehran had been an artistic Mecca. Yet, the revolution changed everything.

The Ayatollah transformed Iranian society in months, and Marjane had witnessed her female students exchange their pencil skirts and Rolling Stones albums for burquas and Qurans, and the men digest an increasingly militant, extremist Islamist zeal.

Within a year, Tehran was no longer safe to raise her daughter and to teach what had now been deemed Western propaganda.

One night, their years of savings were given to a man who Bahram trusted could put them on a plane, and with a small suitcase, they clandestinely fled, unaware until they'd landed in Copenhagen that Denmark was their new home.

And she'd explain how, in the following months, the days were filled with news of disappearances only to be later confirmed as death or imprisonment. That her colleagues were murdered for their refusal to "conform."

"Which is worse than death." She said with an unexpected defiance.

And I'd watch this brilliant woman, this brave, broken lioness, stand at the edge of her mind, staring into the abyss of her past, seeing the faces of her sisters who were murdered by the military police, vanish into the madness of a regime perpetuated by lunatics.

This woman, an intellectual in her own country, an aspiring writer and poet, had spent the last 30 years pumping petrol and being held up at knifepoint on her graveyard shifts at the supermarket. This brilliant, lonely mind deteriorating daily, propped up by a scaffolding of antipsychotics and biblical verses.

Some mornings, when she'd return from her job delivering mail, she'd be too exhausted to talk much. So we'd sit and eat cheese and cucumber on brown bread, smiling in silence, confirming that language is but a shadow of the true connection between people.

And the last time I saw her, we read the bible together in the living room, with an Arabic/English translation she'd gifted me. It was a previously unthinkable activity, yet seeing the strength those verses provided her changed my mind about religion forever.

We'd sit in silence as, now and then, I'd excitedly read a line or two aloud, watching her smile and knowing that she'd digested every word in her loneliness.

I knew then that our suffering, if endured with integrity, produces the most immense souls.

As I hugged her goodbye, knowing I'd never see her again, she said, "I will pray for you."

Goodbye, Marjane,

I don't know how we understood each other so well. It still makes me stop and think. But, I often feel your prayers.

Wherever you are now, I pray for you too.