The عاهل of Luxor

We never saw his eyes, yet he was the self-acclaimed king (el-malik; الملك) of Luxor, and by the end of the afternoon, we believed it.

The morning had been a frenzy of fleeting yet infuriating interactions. We'd left our hotel high on copious quantities of Egyptian coffee and been offered everything from donkeys to special massages as we meandered to the temple.

What began as a stroll through the streets was increasingly becoming a treading in the endless rapids of understandably opportunistic locals eager to exploit two twenty-something westerners with backstreet brothels and alabaster trinkets that seemed to endlessly spill out of their gallibayas.

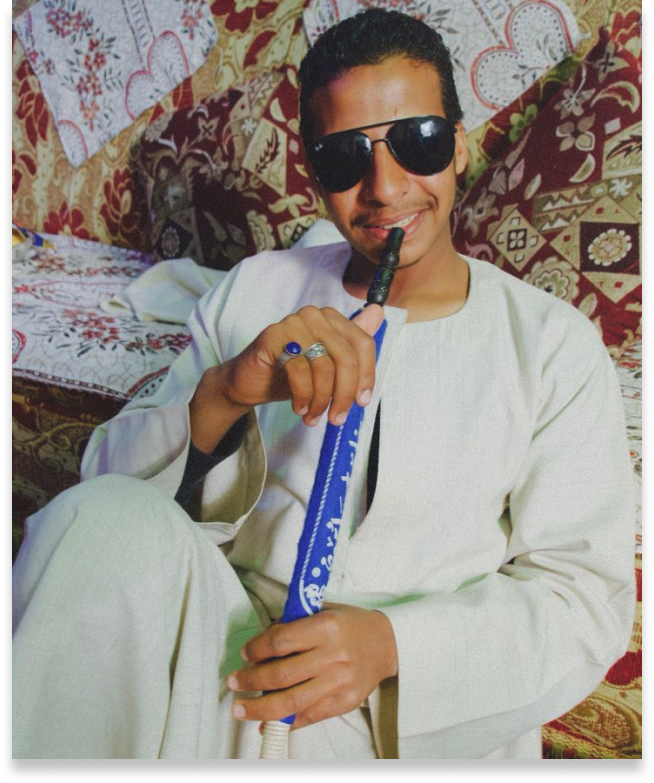

After 15 minutes, we were engulfed by a fuzzy static of Arabic music blaring out of a beaten-up carriage connected to the most indifferent horse we'd ever seen. As he brought the horse to a casual halt in front of us, the owner, a young man in large, tinted black aviators, called out in a deep, rhythmic slur.

"Brotherssss! My brotherrrs! Welcomme to Luxor! Let the eahil show you his kingdom. Come, come into my Ferrari!"

Now, I should clarify that this is not particularly strange in a country where the average street vendor oozes charisma and sleaze, a country where I was once sincerely offered a thousand camels to part ways with my mother. Yet our man looked like a Cuban porn star cross-dressing as Aladdin, and, unlike his colleagues in the horse and carriage mafia who trawled Luxors West Bank, he looked 15 years younger and emanated a certain swag and sincerity at once enigmatic and endearing. He had style.

After a hilarious exchange, we relented and accepted a seat in his Ferrari to Karnak Temple.

The following ten minutes escalated exponentially.

Beginning with the usual superficial, transactional ascertaining of nationalities and declining tour offers, the three of us quickly realized that we were in a like-minded company, and, being 24, the conversation adjusted accordingly. Mohommad claimed to have enjoyed an abundance of foreign sexual conquests. We giggled hysterically as he gloated relentlessly, listing notable highlights and peculiarly specific details from his debauched Cassanovic career. He insisted that he was the king of the ancient city, vulgarities spilling from his mouth in English with ease, a rarity among traditional Egyptians.

We soon realized he'd been driving us in circles. The unexpected charisma of our new friend had enraptured us.

Eventually, we entered Karnak, one of the most elaborate temple complexes on earth. Your perception of modern architecture irreversibly alters after standing at the feet of the columns at Karnak.

Aside from the pyramids, Karnak is perhaps Egypt's most enduring and profound mystery. The absurdity of the old rope-and-pully-slave paradigm is all-encompassing as you realize that modern engineers would struggle to lift even one of the larger stones at Karnak. We left with the profound realization that there are gaps in our history and that our culture, as proposed by Hancock, has a deep amnesia.

Struck by the majesty of the temple, we'd almost forgotten about the عاهل, yet he was waiting just outside the entrance, feeding his horse, cigarette casually dangling out the corner of his mouth.

Boarding the Ferrari, it was obvious that his energy had changed entirely. Our man had done some thinking in our absence and immediately proposed to host us at his house, where he assured us we could eat local food, drink beer (notoriously difficult to find outside of hotels in Luxor), and smoke as much hashish as we wanted all afternoon.

Now, if I've learned anything on the road, it's that when moments like this spontaneously present themselves, you run with them.

Twenty minutes later, we were smoking flavored shisha on the floor of a small, modest living room in an apartment in the back streets of town. The room was sparsely furnished, but for a low oriental coffee table, rugs, a small TV, and a haggard boombox Mohammad was fiddling with every two seconds while Arabic pop music wailed across the room, intermittently mixing with the noise in the street two stories below through the open window.

The King of Luxor lived with his sister and her family. The poor woman was just as surprised as we were to find us in her living room, yet she greeted us with dignified generosity, readjusting her hijab as she hurried away into the kitchen to prepare sweets.

The unfortunate reality for many women living in traditional Egyptian families is that rigid, archaic social roles perpetually bind them to faceless domesticity. The thought of his sister joining us for a drink and smoke in the living room would have been unthinkable for Mohammad, yet in our world, it was commonplace.

Once Mohammad had fixed a steady stream of unidentified local music perforating our eardrums, he busied himself by the window, throwing a bucket connected to a long piece of rope out the window and smiling at us as he made several very sharp whistles, each time followed by a few Arabic words. We drank tea, intently watching him lightheaded from the tobacco billowing out of the elaborately decorated shisha at our feet.

Within a few minutes, the music was pierced by a shrill, higher-pitched whistle from below the window, and he rushed to reel the rope with the efficiency of a military commando, presenting a large, grimy white bucket on the floor. We eagerly looked inside, taken by the surreality of what was unfolding before us. It was filled with six cold beers and a small, brown substance wrapped in plastic. Hashish.

We erupted into hysterics as he smiled ear to ear and took a long, deep inhale of tobacco before calling abruptly to his sister, who obediently presented two glasses.

Mohammad began to undo the plastic, separating small chunks of the hash as he gently placed it onto the coals. As the room filled with a thick, familiar haze, we began to settle into our new environment, sharing music and boastful stories with an unashamedness particular to young men momentarily freed from the confines of culture.

Life was tough for his family in Luxor, but they were happy. He had been a 'Ferrari' driver since his early teens, and he had met many foreigners but knew he would never earn enough money to ever be a foreigner himself. We spent several hours smoking and discussing Egyptian history, Islam, music, and life in Australia.

His sister only emerged from the kitchen once to offer more food or remove the dishes, something we cautiously questioned him about. Yet, he was surprisingly honest and aware of his culture. He knew Western ideals differed greatly, but in Luxor, this was how it was for women, something you could tell he had grown up digesting as a mere fact of life.

That his sister was practically bound to serve him and any guests he brought home was unsettling, but it was a powerful reminder of the continual reality of the inequity and disparity that exists in much of the world that remains firmly patriarchal.

Despite this, Mohammad possessed a discerning intelligence and keen wit that often accompanies people who have grown up working in the streets in these countries as children.

The bucket seemed bottomless, and we were endlessly captivated by the speed at which a whistle and a rope out the window could procure alcohol in a country where it was Haram.

Whatever was going on, our man surely had things sorted, and, as the hours wore on, the hash started to obscure reality, and the aviators remained glued to Mohammad's face, we began to see him with an increasingly mysterious awe.

In those hours, and in the ones proceeding as we lay in our beds back at the hotel staring at the ceiling, it had felt like we had encountered a magician from the Arabian Nights, a jester with almost shamanic powers. But, as time clarified reality, I understood that Mohammad was just a young guy like us, curious about the world and excited to share his culture with authentically interested people. And, of course, he was a savvy businessman. The عاهل knew it would be profitable, and it was.

Leaving the following day, we tipped him our remaining Egyptian pound as we stumbled into the dusty streets. Enough, apparently, to find him driving a new "Ferrari" with the same worn-out horse the following morning as we left Luxor.

"My friendss!! Look. This is my Bugati!"