What Are Mandalas? And Why Are They Everywhere?

The universal prevalence of mandala patterns in the collective human unconscious is both undeniable and mysterious. The mandala is found across all cultural strata: art, architecture, religion, philosophy, mathematics, and myth (to name a few) on every continent. It is, as Jung states in his Memories, Dreams, and Reflections, “an archetypal image whose occurrence is attested throughout the ages.”[1]

However, serious research on mandalas remains scant, and an online search for information on such a profoundly culturally intertwined phenomenon reveals little more than a swath of cheesy promotional websites catering to the making of “personal mandalas for mindfulness,” perhaps indicative of the shallow self-obsession so often characterizing western post-modernism, or what Joseph Campbell called the “New Age Razzle Dazzle.”

Here, I hope to steer you away from mandala adult coloring books, present you with what we know about the mandalic phenomena, and ignite a curiosity for all we don’t.

The word mandala derives from the Sanskrit verbal root mand (loosely translated in English as to mark off, decorate, set off) and the Sanskrit suffix “la” (loosely translated to mean circle, essence, sacred center).[2] The Encyclopedia Britannica describes mandalas as “a representation of the universe, a consecrated area that serves as a receptacle for the gods and as a collection point of universal forces.”[3]

The first appearance of the term mandala is as the name of sections of the Indian Rig Veda,[4] the oldest of the four Vedas. The Vedas (Veda) can be translated as “knowledge,” and they represent the oldest Hindu scriptures and Sanskrit literature.[5] Following their transmission from the Vedic rishis (sages) who, during the Vedic period, are said to have heard the primordial sounds of the universe from Brahman (the ultimate universal reality) during intense mediative states, the Vedas were supposedly orally transmitted from father to son or guru to student.[6] The earlier sections of the written text are considered among the oldest texts in any Indo-European language.[7]

The Rig Veda contains ten chapters (mandalas), each containing 1,028 hymns of 10,600 verses (sūktas), which transmit the universal nature of reality.[8] Each mandala in the Rig Veda was designed to harness and draw the reader's energy towards the supreme reality, facilitating their relinquishing of illusions and false perceptions of egoic consciousness in the process. As Brahman transcends comprehension, this reality appeared to people as visual and perceptible forms, as did the later deities who are manifestations of different aspects of energy. Eventually, drawings designed to illustrate the nature of the visions received accompanied the text, and it is here that the oldest symbolic mandalas supposedly emerged. These symbols served the same function as their written (and verbal) predecessors: representations of the cosmic order and facilitators of the ascension of consciousness.[9]

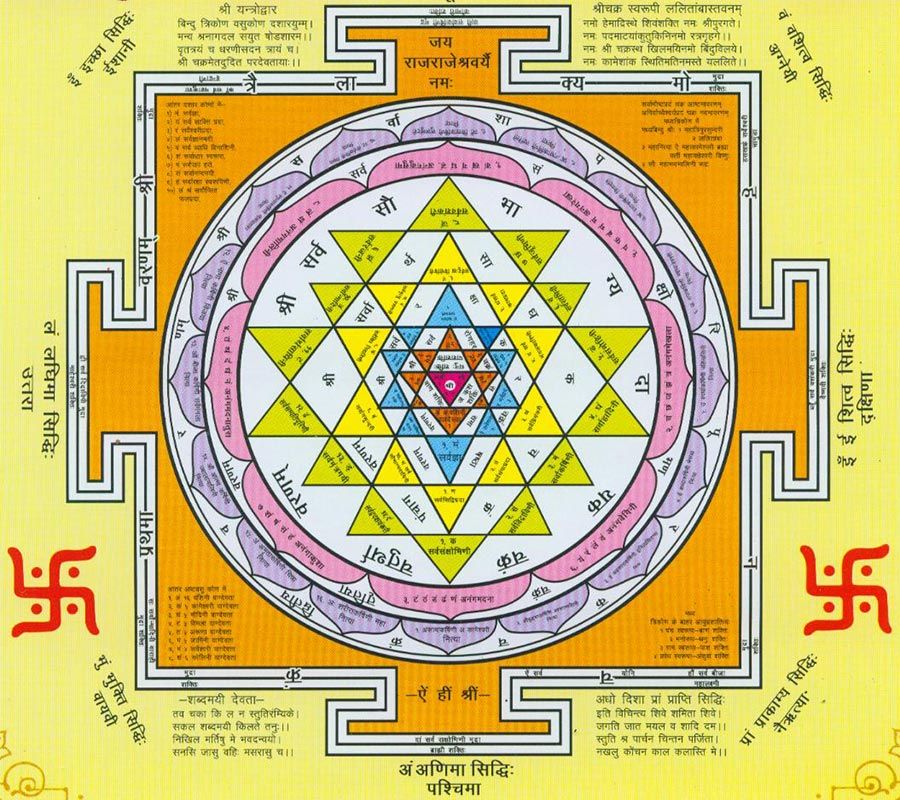

The basic Hindu mandala also called a yantra, is typically formed from sacred geometrical patterns. It often has a radial balance, and it is represented by a square with four gates containing a circle with a center point. Each gate is in the general shape of a T.[10] Each Hindu deity is represented by a mandala or yantra, enabling the worshipper to internalize the specific energy through meditation.

However, whilst serving a similar energetic function, yantras are usually smaller than mandalas. They can be represented as two- or three-dimensional geometric compositions used in sadhanas, puja, or meditative rituals and may also include a mantra. According to Indian scholar Khanna Madhu, “Yantras function as revelatory symbols of cosmic truths and as instructional charts of the spiritual aspect of human experience”[11] Furthermore, in Hindu tantric practice, Khanna describes the yantra as being “a reality lived” stating that “every symbol in a yantra is ambivalently resonant in inner–outer synthesis, and is associated with the subtle body and aspects of human consciousness.”[12]

So, mandalas are a form of ancient Hindu symbolism?

Yes and no.

Where things become really fascinating is that the mandala is essential to the central myths and practices of many cultures throughout history, making its presence within the collective psychic domain difficult to define. Below, I will highlight numerous prominent examples.

Perhaps the most prevalent use of the mandala outside of Hinduism is in Buddhism. Beginning with Siddhartha Gautama’s illustration of the cycle of samsara (the karmic cycle; wheel of life), Buddhist mandalas essentially represent the Buddha's vision of the nature of reality and the ultimate reality of his teachings: Human life as the suffering of ignorance, craving, and fear and the nirvanic path toward enlightenment. The forms of mandalas vary across all three Buddhist schools and their derivatives; however, each has used (and continues to use) the mandala to represent and transmit their perception of reality.

Similar to Hindu mandalas and yantras, Buddhist mandalas are designed to have a transformative, meditative focus, whereby the perceptions and consciousness can gravitate spirilicly towards the true nature of existence. Here, the Tantric Buddhist Kalachakra mandala (the Wheel of Time) is perhaps the most well-known representation.[13]

Buddhist mandalas serve the same universal intention of using geometry and concentric circles to harness and raise consciousness. Joseph Campbell states that the Buddha is often placed at the center “as the power source, the illumination source.”[14] to represent the supreme reality of his cosmology. Furthermore, many Buddhist mandalas use illustrations within geometry to represent the soul's progress along the Eightfold Path or Buddha’s journey toward enlightenment. Here, the visuals can be literal or symbolic, and “the peripheral images would be manifestations or aspects of the deity’s radiance.”[15]

Interestingly, over subsequent generations, Buddhist mandalas became increasingly seen as having an energetic resonance of their own, whereby the act of creating the mandala weaved the creator’s energy into the energetic narrative of the symbol and its truths. Therefore, these mandalas came to be perceived as transmissions from higher universal sources. Here, like the original Vedic mandalas, we note the transmission-like relationship with a collective source thread, an observation most famously noted by Jung.

The Tibetan word for mandala is kyilkhor. Kyil means “center,” and khor means “fringe,” “gestalt,” or “area around.”[16] Chögyam Trungpa stated that Buddhist mandalas represent the interdependence of events and that the “interdependent existence of things happens in the fashion of orderly chaos.”[17] Furthermore, Dzogchen Ponlop Rinpoche described a mandala as an “integrated structure organized around a unifying center.”

In Psychology and Alchemy, Jung discusses his visit to the monastery of Butia Busty and his meeting with Lamaic rimpoche, Lingdam Gomchen. During his visit, Jung discussed the Khilkor (mandala) with the lama, and Gomchen explained the symbol as a dmigs-pa (pronounced “migpa” in English), “a mental image which can be built up only by a fully instructed lama through the power of imagination.”

Furthermore, Lingdam Gomchen told Jung that “the true mandala is always an inner image, which is gradually built up through (active) imagination, at such times when psychic equilibrium is disturbed or when a thought cannot be found and must be sought for because it is not contained in holy doctrine.”[18] Jung’s contribution to the study of mandalas will be discussed in further detail later.

The sand mandalas of Tibetan Buddhism are another notable mandalic form. In the great Tantric monasteries outside of Lhasa, Monks require several years of training to create the sand mandalas, and they are made by placing colored powder over a white chalk geometric blueprint.[19] Typically, a sand mandala is created by four monks sequentially working on each of the four traditional quadrants, and the physical geometry of the mandala represents a tantra.

Despite popular belief in the West, tantra refers to an esoteric system, theory, or method, and the majority of tantras have nothing to do with sex. Sand mandalas are believed to facilitate personal enlightenment and generate peace, wisdom, and liberation for all beings. One of the sublimely peculiar aspects of the sand mandala is its ritualistic destruction after weeks of painstaking creation. This act represents the impermanence of existence, the central Buddhist theme.

Mandalas are also deeply embedded within the Christian tradition, where they are most commonly found in the form of stained glass rose windows, frescos with animal images representing the apostles, representations of the astrological zodiac, and depictions of saints surrounded by halos of light. After analyzing Christian symbols, Jung concluded that Christ was a mandala-like symbol for the Self and psychic development. Perhaps the symbol of Christ on the cross is a variant of the representation of the same energetic ascension from the mundane to an integration with the universal matrix of reality that Christians call god.

Furthermore, the Mandorla, also known as the “Vesica Piscis,” is an ancient symbol commonly used within the medieval Christian period. The symbol contains two circles overlapping each other, and it is similar to the image of mandalas merging until an almond shape is formed in the center.[20] This form of mandala is said to represent the interactions and interdependence of opposing realities and energies and the circles are considered to symbolize the relationship between spirit and matter or heaven and earth[21]

Mandala designs are also evident in the “illuminations” of Hildegard von Bingen, the 12th-century nun and pre-renaissance polymath. These illuminations are believed to represent Hildegard’s prophetic visions, and her famous “fiery cosmic egg” echoes a strikingly similar narrative to the use of Vedic mandalas to convey archetypical universal transmissions received by the Rishis. Furthermore, the use of mandalas is also found within the works associated with Rosicrucianism and alchemy, a thread first noted by Jung.

Mandalas within architecture have been used by cultures around the world. The Roman Pantheon, constructed in the 2nd century AD, takes the form of a mandala, as does the Papal Basilica of St. Peter, constructed in the 16th–17th centuries and located in the Vatican. However, the use of labyrinths within Christian architecture is particularly astounding. The best example of this is commonly known as the “Chartres pattern,” named after the labyrinth on the floor of the Chartres cathedral, constructed in France during the early 13th century. The labyrinth has a circular shape and is formed from 11 concentric circles. Interestingly, the labyrinth forms a series of convolutions as it reaches the center, where a hexafoil (petalled rosette) sits as a representation of God.[22]

The Chartres labyrinth facilitated “pilgrimages” for those unable to reach the Holy Land during the Middle Ages, and its similarity in function to the three-dimensionality of certain Hindu shrines and temples and Japanese Shinto paradises, or kami, is remarkable. The word dojo is typically considered to mean mandala in Japanese Zen Buddhism, meaning any place where transformation occurs.[23]

Furthermore, there are numerous examples of “Classical” or “Cretan” mandalaesque labyrinth patterns found in antiquity,[24] and the labyrinth rock carving found at Meis, Spain, could have been created as early as the late Stone Age or early Bronze Age. On the island of Java, the 9th-century Boronudor Temple was intended to function as an interactive mandala-yantra where people could walk through the structure in a particular pattern while being influenced by the energy of the geometry and symbolism, thus facilitating enlightenment.[25]

Islamic geometrical designs and mosque ceilings highlight the sublime psychic power of sacred geometry within mandalas, and such mandalas often adorn the covers of the Koran, The Torah, the Tanakh, and the Bible. In addition, the Persian Ishtar star symbol, the heptagonal Seal of God, the soapstone seals of the Indus Valley culture, and the Mesopotamian cylinder seals are believed to be forms of mandalas whereby a central image is accompanied by symbols that draw the energy inward. Mandalas can also be found in Celtic knot works and spiral and circular symbols, in addition to the ancient Druidic symbols that preceded them.

Turning to the Americas, the Mayans used a mandala for their astrological calendar and their Tzolk’in, and the Aztecs as their Sun Stone. In the Power of Myth, Joseph Campbell states that “among the Navaho Indians, healing ceremonies were conducted by way of sand paintings, which were mostly mandalas, on the ground and then the person who is to be treated moves into the mandala.”[26] He explains how the mandala is used by these communities to align the sick person with a mythological context to heal their psyche.

In fact, similar to most indigenous populations around the world, the Native American worldview was inextricably bound with the mandala and the interplay of circular forms: “You have noticed that everything an Indian does in a circle, and that is because of the Power of the World always works in circles, and everything tries to be round.”[27] Moreover, Northern and Southern American communities used the mandala as direct representations of deities or the cosmos or to symbolize a spiritual journey, psychic energy, or as energetic protection against unwanted spirits, as exemplified by the circular hoop design known as a dreamcatcher.

The presence of mandalas is incontrovertible. The question is: why?

Regarding serious attempts to understand and contemplate this question, the most influential modern thinkers are Carl Jung and Joseph Campbell. The re-introduction of mandalas into the modern Western collective consciousness can largely be attributed to their unquenchable curiosity about the psyche and cross-cultural philosophy.

During a particularly dark period of his life, Carl Jung began intense explorations of the unconscious through art. Simultaneously, as a form of self-healing, he “sketched every morning in a notebook a small circular drawing, a mandala” stating that it “seemed to correspond to my inner situation at the time.”[28] Through his study, coupled with his daily sketches, Jung noticed the prevalence of the circle motif throughout various cultures and religions.

Furthermore, he also found that these geometries were a potent healing tonic: “With the help of these drawings, I could observe my psychic transformations from day to day.”[29] Given his awareness of Vedanta, he called the circular drawings he created “mandalas.” Naturally, Jung set about integrating the practice as a pedagogical device into a clinical setting, where he observed the universality of the mandalic symbolism through the similarities of mandalas created by patients from various cultures. He also noted the healing capacity of the symbols, stating in Mandala Symbolism that “a rearranging of the personality is involved, a kind of new centering.”[30]

Jung believed that the mandalas reflected the psyche at their conception and that their astounding prevalence across cultures derives from their archetypal relationship with the universal subconscious: “The mandala signifies the wholeness of the Self. This circular image represents the wholeness of the psychic ground or, to put it in mythic terms, the divinity incarnate in man." [31]

Having recognized the archaic, psychic element of mandalas, he stated that it is “beyond question that these Eastern symbols originated in dreams and visions and were not invented by some Mahayana church father.”[32]

Jung defines the universality of the mandala as “an instrument of contemplation”[33] and highlights the universal spiritual and psychological importance of the journey from the outside (the external world) toward the center (the self) to achieve total individuation—to recognize and become the self. He highlighted the occurrence of similar circular patterns within Dervish monasteries in the form of Dance figures, and he observed that they appear “as psychological phenomena they appear spontaneously in dreams, in certain states of conflict, and in cases of schizophrenia.”[34]

However, perhaps what is most intriguing about Jung’s theory is his recognition of the number four in mandala symbolism. Jung found that his patients consistently created mandalas with motifs related to the number four. He called these a “quaternity,” and the symbols typically manifested as a cross, a square, an octagon, or a star. Here he noted the frequency of a similar “quaternity” found in alchemical texts known as the “squaring of the circle” or the “quadratura circuli,” a problem that had fascinated and challenged the medieval mind.[35]

Consequently, this prevalence of the quaternity among his patients led Jung to study alchemical works, and here he found many examples of the significance of the number four, such as the four main steps in the alchemical process: nigredo (black), albedo (white), citrinalis (yellow), and rubedo (red).[36] In addition, he noted that alchemical processes have fourfold properties (hot, cold, wet, and dry), while matter is considered a combination of the four elements: earth, air, fire, and water.

Furthermore, Jung observed that the alchemical Philosopher’s Stone was four-fold in nature, "The lapis is called a ‘sacred rock’ and is described as having four parts."[37]

Think it’s getting weird? Well, buckle up, of course, Jung goes deeper.

Jung identified the psychic prevalence of four-fold symbols and systems in religion, myth, history, and culture. He noted that there are four winds (Boreas, Eurus, Notus, Zephyrus), four seasons, four cardinal directions, four Biblical Evangelists, four letters in the sacred name of God (YHVH), four ancient ages (gold, silver, bronze, iron), and four humors in the medieval composition of the human body: sanguine (blood), choleric (yellow bile), phlegmatic (phlegm), melancholic (black bile).

It was this four-fold nature of the mandala, the psychic “squaring the circle,” Jung argued, that made it such a powerful archetype in the collective psyche. It represents the eternal journey of the universal energetic spiral—of return to the source and a return to a higher order of configuration. Integrated and more complete. The same eternal pattern within a nautilus, an ammonite, or a galaxy. Fibonacci’s golden ratio exists within realms of the collective unconscious. Here, Jung emphasizes the “symbol of the opus alchymicum because it breaks down the original chaotic unity into the four elements and then combines them again in a higher unity”[38]

Ultimately, Jung believed that the mandala is an unconscious archetype representing a relationship between our psyche and the true matrix of reality, and it symbolizes the restoration of the previously existing order. Consequently, he theorized that the archetypal nature of mandalas was responsible for their universal prevalence in the psyche.

However, he believed the mandala also serves the creative purpose of giving expression and form to a currently inexistent (or indefinable) potentiality, something new and unique. The process is that of the ascending spiral, “which grows upward while simultaneously returning again and again to the same point.”[39]

Writer and professor Joseph Campbell also noted the strange cross-cultural similarities in the use of the mandala. He observed that “every religion in the world employs the circle as a metaphor” and that “somehow the circle suggests immediately a completed totality, whether in time or in space.”[40] Plato, the father of Western thought, believed that the soul was a circle, and curiously, da Vinci’s Vitruvian man is placed within a circle.

Campbell defined a mandala as being coordinated or symbolically designed so that it has the meaning of a cosmic order. Like Jung, he believed that mandalas had a psychically ordering principle and that the symbolic geometries within the mandala are a “kind of discipline for pulling all those scattered aspects of your life together, finding a center and ordering yourself to it. So, you’re trying to coordinate your circle with the universal circle.”[41]

On the universal similarities of mandala creation, Campbell states that there are only two possibilities: “One is by diffusion, that an influence came from there to here, and the other is by separate development. And when you have the idea of separate development, this speaks for certain powers in the psyche that are common to all mankind. Otherwise, you couldn’t have—and to the detail, the correspondences can be identified, it’s astonishing when one studies these things in depth, the degree to which the agreements go between totally separated cultures.”[42]

Through his life-long research on world mythology, Campbell believed that the mandala was a representation of indescribable energy. A point of focus that worked on the psyche, providing “reflections of spiritual and depth potentialities of every one of us. And that through contemplating those, we evoke those powers in our own lives to operate through ourselves.”[43]

Jung and Campbell's pioneering work influenced the use of mandalas in modern therapy.

Unsurprisingly, since Jung’s re-discovery of the healing power of Mandalas, a substantial research field has developed around the subject of art therapy for patients. Consequently, many variations of mandala use in art therapy have been employed. The implementation of mandala creation in art therapy appears to successfully reduce the symptoms of psychological illness and may be beneficial for the development of the individuation process.

Specifically, research is being conducted on the efficacy of mandala creation in healing particular trauma-related illnesses. Studies have shown that mandala creation has led to reduced anxiety in various contexts in individuals with dissociative disorders (Cox & Cohen 2000), ADHD (Smitherman-Brown & Church 1996), dementia (Couch 1997), and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD; Henderson, Rosen, & Mascaro 2007).

Furthermore, another study noted a reduction in anxiety and trauma in subjects who created a mandala drawing compared to those who created a random drawing on a blank sheet of paper (Henderson, Rosen, & Mascaro 2007). Interestingly, replication studies have also confirmed that coloring pre-drawn mandalas reduced individuals’ anxiety (Kersten & van der Vennet, 2010; van der Vennet & Serice 2012).

This is unsurprising when we consider Jung’s conclusions in his work with patients and his intellectual journeys into the mysteries of the mandala archetype: “…it is easy to see how the severe pattern imposed by a circular image of this kind compensates the disorder of the psychic state—namely through the construction of a central point to which everything is related, or by a concentric arrangement of the disordered multiplicity and of contradictory and irreconcilable elements. This is an attempt at self-healing on the part of Nature, which does not spring from conscious reflection but from an instinctive impulse.”[44]

Furthermore, the interest in mandala coloring books, originally shown to be an effective stress management tool for young adults and adults with intellectual disabilities, has increased among the general population, perhaps further indicating the collective magnetism of this archetype as a healing, introspective energy. Furthermore, studies have shown that mandalas reduce mood-related negativity (Babouchkina & Robbins 2015); increase self-awareness, psychological well-being, and authenticity (Pisarik & Larson 2011); assist with trauma integration (Kometiani & Farmer 2020); and improve PTSD symptoms (Henderson et al. 2007).

Finally, we arrive at perhaps the least studied and most fascinating aspect of mandalas: The proliferation of mandala images during the psychedelic experience.

The connection between psychoactive plant use and almost every culture that has shared this planet is universally proven and accepted. Far from being an anthropological deduction, it appears to be sheer common sense and humility. If current cultures share the same desire to expand their consciousness, it seems a logical assumption that our ancestors did, too: Humans have a love affair with intoxication. An obsession with altered states.

Therefore, I will not expand on that here. Instead, this section will map the connection between mandalas and psychoactive experiences.

Even before the psychedelic discussion begins, it is worth noting that visions of mandalas have been reported in almost every facet of psychic experience. As Jung and Campbell noticed, they are a universal motif in dreams, art, and mythologies.

History is littered with countless reports of mandalic visions during mystical and near-death experiences, fasting practices, sensory deprivation techniques, and mediation practices, in addition to visions of mandalas as a result of disorders like epilepsy and schizophrenia.

Furthermore, mandalas, geometrical patterns, and hallucinatory images have even been found in petroglyphs and cave paintings and throughout indigenous art forms, such as the Dreamtime paintings of the Indigenous Australians. In numerous shamanistic traditions, they have been considered messages from the spirit world.

Users of psychedelics frequently report visions of mandalas, Yantra-like geometries, fractals, and otherworldly forms during their experiences. The universality of these visions and the consistency in their description is very curious indeed.

The majority of the information on plant-induced visions has been traditionally culturally protected within the bounds of ritual and initiatory rites. In this sense, native communities around the world have had relationships with these plants for dizzying periods, and consequently, a deep and immeasurable connection with mandalic and other geometric visions has been carried through their lived experience, dance, mythologies, art, and shamanic practices.

However, the systematic study of geometric hallucinations during the psychedelic experience was first studied by German-American psychologist Heinrich Klüver, whose interest in visual perception saw him experimenting with the peyote cactus—the cactus later re-introduced into the Western consciousness by the American writer Carlos Castaneda.

The psychoactive ingredient of peyote, mescaline[45] is known for its ability to induce profound visual hallucinations, and Central American communities have used the plant ethnobotanically and medicinally as the center of their shamanic rituals for at least several millennia. After ingesting peyote in the laboratory, Klüver observed the repetition of geometric forms taken by the hallucinations. Consequently, he classified them into four “form constants”: tunnels and funnels, spirals, lattices including honeycombs and triangles, and cobwebs.[46]

In fact, Professor Jack Cowan analyzed cave art from around the world, and whilst no theory of psychoactive plant usage was discussed, he stated that the geometric patterns are signs of hallucinations. Furthermore, archaeologist David Lewis-Williams argues in his book, The Mind in the Cave, that the blob, dot, and lattice patterns in the Chauvet cave are also hallucinatory.

Lewis-Williams also claims that entoptic forms can be found in San Bushmen rock art and Palaeolithic rock art. In addition, LSD-induced visions of funnel and spiral images were studied by Oster (1970), and by Siegel (1977). Both researchers noted extraordinarily similar images, suggesting that the geometric hallucinations generated by LSD are universal.

But why are these "hallucinations" mandalas?

When considering mandalas within psychedelic visions, it is interesting to note Campbell’s “two options” to describe the university of these forms, presented earlier: “diffusion, that an influence came from there to her,” and “separate development.”[47] The psychedelic experience presents reoccurring motifs that are unquestionably embedded within the ancient traditions and cultures of the world. Furthermore, the mandala is an essential geometric blueprint found within all natural systems. However, this begs the question: do we create the visions based on influences in our psyche, or are we connecting with an ethereal web of motifs and archetypes that transcends comprehension? The answer remains wonderfully elusive.

What is certain is that the use of mandalas or mandala-like geometric symbolism is so universal that it is impossible to note even a fraction of the representations throughout history. The mandala seems to be an integration pattern, a gestalt, and many people and cultures insist that intelligence, or form of consciousness, emanates from these patterns —a striking similarity to the Vedic and Buddhist belief systems of mandalas as conduits for higher energies.

Whatever the mandala is, it represents a link between our consciousness and a higher ordering principle. The universality of the mandala, if anything, highlights our collective human connection and perhaps a link to our archaic origins deep within the psyche of our species.

Notes

[1] Jung, Memories Dreams Reflections, pp. 334–335

[2] Asia Society. “Mandala: The Architecture of Enlightenment.”

[3] Encyclopedia Britannica, 15th edition, Volume 6, p. 555.

[4] INDIAN CULTURE, “Handbook to the Study of the Rigveda: Part II-The Seventh Mandala of the Rig Veda.”

[5] Radhakrishnan; Moore, A Sourcebook in Indian Philosophy (12th Princeton Paperback ed.).

[6] Hexam, Understanding World Religions: An Interdisciplinary Approach.

[7] Bryant, The Yoga Sutras of Patañjali: A New Edition, Translation, and Commentary. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. pp. 565–566.

[8] Werner, A Popular Dictionary of Hinduism.

[9] Mark, “Mandalas.”

[10] Kheper, “The Buddhist Mandala – Sacred Geometry and Art.”

[11] Madhu, Yantra: The Tantric Symbol of Cosmic Unity, p. 12.

[12] Ibid., pp 12–22

[13] Newman, The Wheel of Time: Kalachakra in Context, pp. 51–54, 62–77.

[14] Campbell; Moyers, The Power of Myth.

[15] Ibid.

[16] “Crazy Wisdom – Chogyam Trungpa – Transcending Madness – Beezone Library,” n.d.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Jung, Psychology and Alchemy, paragraph 123.

[19] Bryant, Wheel of time Sand Mandala.

[20] Fletcher, Musings on the Vesica Piscis.

[21] Ibid.

[22] Høyrup, Geometrical Patterns in the Pre-classical Greek Area. Prospecting the Borderland between Decoration, Art, and Structural Inquiry(PDF). Revue d'histoire des mathématiques.6 (1): 5–58.

[23] Suzuki, Chapter 9: The Meditation Hall and the Monk's Life, An Introduction to Zen Buddhism. Grove Press. pp. 118–132.

[24] The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. “Labyrinth | Architecture.”

[25] Wayman, Reflections on the Theory of Barabudur as a Mandala.

[26] Campbell; Moyers, The Power of Myth, 1988.

[27] Neihardt, Black Elk Speaks.

[28] Jung, Memories, Dreams, Reflections, pp. 195–196.

[29] Ibid.

[30] Jung, Mandala Symbolism: (From Vol. 9i Collected Works). pp. 71–100.

[31] Jung, Memories, Dreams and Reflections, pp. 334–335

[32] Jung, Psychology and Alchemy, paragraph 124.

[33] Mark. “Mandala.” World History Encyclopedia.

[34] Jung, Mandala Symbolism: (From Vol. 9i Collected Works), pp 3–5.

[35] Jung, Mandala Symbolism: (From Vol. 9i Collected Works), pp 71–100.

[36] Von Franz, Alchemy: An Introduction to the Symbolism and the Psychology, p 196.

[37] Jung, Collected Works of C.G. Jung, Volume 9 (Part 2).

[38] Jung, Collected Works of C.G. Jung, Volume 12: Psychology and Alchemy, pp. 124–125.

[39] Jung, Man and His Symbols, p 225.

[40] Campbell; Moyers, The Power of Myth, 1988.

[41] Ibid.

[42] Ibid.

[43] Ibid.

[44] Jung, Mandala Symbolism: (From Vol. 9i Collected Works). pp 71–100.

[45] Salak, Lost Souls of the Peyote Trail.

[46] Ibid.

[47] Campbell; Moyers, The Power of Myth, 1988.

Works Cited

Caulfield, Jack. “How To Do Thematic Analysis.” Scribbr. September 6, 2019. https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/thematic-analysis/.

Covey, Stephen. The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People. New York: Free Press, 1989.

Asia Society. “Mandala: The Architecture of Enlightenment,” n.d.

https://asiasociety.org/mandala-architecture-enlightenment.

Bryant, Barry. Wheel of Time Sand Mandala. San Francisco: Harper San Francisco, 1992.

Campbell, Joseph; Moyers, Bill. D. The Power of Myth, 1988.

“Crazy Wisdom – Chogyam Trungpa – Transcending Madness – Beezone Library,” https://beezone.com/chogyam-trungpa-rinpoche/razors_edge.html. March 31, 2023.

Encyclopedia Britannica, 15th edition, Volume 6, Micropaedia, p. 555.

Edwin F. Bryant. The Yoga Sutras of Patañjali: A New Edition, Translation, and Commentary. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2015. pp. 565–566: ISBN 978-1-4299-9598-6.

Fletcher, Rachel. “Musings on the Vesica Piscis,” Nexus Network Journal, 6 (2) 2004: pp. 95–110, doi:10.1007/s00004-004-0021-8.

Høyrup, J, “Geometrical Patterns in the Pre-classical Greek Area. Prospecting the Borderland between Decoration, Art, and Structural Inquiry,” Revue d'histoire des mathématiques. 6(1) 2000: pp. 5–58.

INDIAN CULTURE. “Handbook to the Study of the Rigveda: Part II-The Seventh Mandala of the Rig Veda.” March 31, 2023. https://www.indianculture.gov.in/rarebooks/handbook-study-rigveda-part-ii-seventh-mandala-rig-veda.

Jung, C. G. Collected Works of C.G. Jung, Volume 9 (Part 2), Aion: Researches into the Phenomenology of the Self. Princeton University Press, 2014.

Jung, C. G. Man and His Symbols. Dell, 1964. p 225.

Jung, C. G. Mandala Symbolism: (From Vol. 9i Collected Works). Princeton University Press, 2017.

Jung, C. G. Memories Dreams Reflections, 2010.

Jung, C. G. Collected Works of C.G. Jung, Volume 12: Psychology and Alchemy. Princeton University Press, 1980. pp. 124–125.

Khanna Madhu, Yantra: The Tantric Symbol of Cosmic Unity, Thames and Hudson. 1979. p. 12.

Kheper. “The Buddhist Mandala – Sacred Geometry and Art.” April 1, 2023. http://malankazlev.com/kheper/topics/Buddhism/mandala.html

Mark, Joshua J. “Mandala.” World History Encyclopedia, April 1, 2023.

https://www.worldhistory.org/mandala/.

Neihardt, J. G. Black Elk Speaks. University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln and London: 1932, 1961, 1979.

Newman, J. The Wheel of Time: Kalachakra in Context. Geshe Lhundub Sopa (ed.). Shambhala, 1991. pp. 51–54; 62–77. ISBN978-1-55939-779-7

Radhakrishnan, Sarvepalli; Moore, Charles. A. A Sourcebook in Indian Philosophy. 12th Princeton Paperback ed. Princeton University Press, 1957. ISBN 978-0-691-01958-1.a

Salak, Kira. Lost Souls of the Peyote Trail (published in National Geographic Adventure). March 31, 2023. KiraSalak.com.

Suzuki, D. T. Chapter 9: The Meditation Hall and the Monk's Life, An Introduction to Zen Buddhism. Grove Press. pp. 118–132.

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. “Labyrinth | Architecture.” Encyclopedia Britannica, March 31, 2023. https://www.britannica.com/technology/labyrinth-architecture#ref227997.

Von Franz, Marie-Luise. Alchemy: An Introduction to the Symbolism and the Psychology. Inner City Books, 1980. p 196.

Wayman, A. Reflections on the Theory of Barabudur as a Mandala, Barabudur History and Significance of a Buddhist Monument. Berkeley: Asian Humanities Press, 1981.